|

| Today's guest nutrition blog comes from former Cressey Performance intern Tyler Simmons.

“It’s best to eat 5 - 7 times a day."

"Eating every three hours fuels your metabolism."

"If you skip meals, your body goes into 'starvation mode,' you gain fat, and burn muscle for energy.”

Chances are that you’ve probably heard something like the above statements if you’ve read anything about diet or exercise in the last ten years. Many of you (myself included) probably spent a lot of time preparing and eating meals, in the hopes of optimizing fat loss and better muscle gain.

What does the data really show about spacing out your meals? When I started researching the topic of meal frequency in 2010, I assumed there was ample scientific evidence to back up these nearly unanimous claims that smaller, more frequent meals were better than larger, less frequent meals. Boy, was I disappointed.

To my surprise, the scientific literature had some different things to say. My research focused on how changing meal frequency impacts two different things: 1) Metabolic Rate and 2) Weight Loss. What I found was compelling evidence that reduced meal frequency, sometimes known as Intermittent Fasting (IF), could actually help me, so I started an experiment.

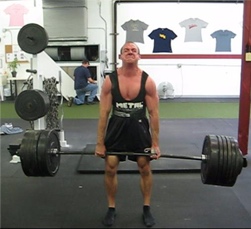

In the summer of 2010 I was living in Alaska doing construction and labor, as well as doing off-season training for Track and Field (sprinting, jumping, and lifting). For years I had focused on eating every 2-3 hours, but based on my new findings, I decided to limit all omy food intake to an 8-hour window, leaving 16 hours of the day as my fasting portion.

Despite doing fasted, hard labor all day, then lifting, sprinting, and playing basketball, I managed to set records on all my lifts at the end of the summer. Not only was I stronger than ever, but I got leaner too.

Here’s pictures from before and after, about 2 months apart:

Getting lean wasn’t even my main goal; the idea that I could be free from eating every three hours without suffering negative side effects was extremely liberating. No longer was I controlled by arbitrary meal times and tupperware meals in a lunch box. During this summer, I developed the ability to go long periods of time (18-24 hours) without food, and not get tired, cranky, our mentally slow down.

So why didn’t I catabolize my muscles, drop my metabolic rate, and end up looking like skinny-fat Richard Simmons (no relation)?

The Science

The idea that eating several smaller meals is better came from a few pieces of information. The first was because of an association between greater meal frequency and reduced body weight in a couple of epidemiological studies, although this only shows a correlation, not causation. Breakfast eaters are more likely to engage in other health activities, such as exercise, which explains the relationship. In the most comprehensive review of relevant studies, the authors state that any epidemiological evidence for increased meal-frequency is extremely weak and “almost certainly represents an artefact” (1).

The second piece is related to the Thermic Effect of Food (TEF), which is the amount of energy needed to digest and process the food you eat. Fortunately, this is dependent on total quantity of food, not on how it’s spaced, making the distinction irrelevant.

So, now we can see that the supposed benefits from increased meal frequency do not hold up to closer inspection, but why would we want to purposefully wait longer in between meals?

Originally, researchers thought Caloric Restriction (CR) was the bee’s knees. Preliminary research showed that CR slows aging, reduces oxidative damage, and reduces insulin and levels. All good, right? Unfortunately, these benefits come with some nasty trade-offs, including reduced metabolic rate, low energy levels, constant hunger, and low libido, pretty much what you would expect from chronically restricting food intake. These were not happy animals.

Recent research has shown that Intermittent Fasting or reduced meal frequency can convey many of the benefits of CR while avoiding the negative side effects. Some of these benefits include:

- Favorable changes to blood lipids

- Reduced blood pressure

- Decreased markers of inflammation

- Reduction in oxidative stress

- Increased Growth Hormone release

- Greater thermogenesis/elevated metabolic rate

- Improved fat burning

- Improved appetite control

Some of these effects may be secondary to the reduction of calories due to improved appetite control, or they may be primary effects of IF, the research is not conclusive on this yet.

One of the most interesting findings was that contrary to conventional wisdom, reduced meal frequency actually causes an increase in thermogenesis (metabolic rate), which is mediated through the increase of catecholamines (stress hormones), such as adrenaline and norepinephrine (1,2). Yep, you read that right: instead of slowing your metabolism down, it speeds it up. Catecholamines also help with the liberation of fatty acids from fat cells, making them available to be burned as energy.

That’s the “why” and the “how” for some of the effects of IF. Whatever the mechanism for it, IF seems to be effective for at least some people, myself included. But before you rush off to go start fasting 16 hours a day, here are some tips and caveats.

Important Considerations

Many people ask me if IF is good or bad, but as with most things, it depends. IF is not appropriate in certain situations. It can be good or bad, depending on who you are (your current health status/lifestyle) and what your goals are. IF is a stressor on the body; one of the primary effects is an increase in stress hormones. If you’re lacking sleep, eating low quality foods, stressed out about your job, and excessively exercising then don’t start an IF protocol. It will backfire and you will end up fat and tired!

Only experiment with an IF program if you are getting 8-9 hours of sleep a night, eating a high quality diet, appropriately recovering from exercise, and don’t have too many mental/emotional stressors.

As far as what goals this works for, common sense applies here. IF is generally best for people who are already moderately lean and are trying to get leaner. If you’re trying to put on 30 pounds of mass, don’t start IF. If you’re an athlete with a very heavy training load, don’t try IF.

For those of you who fit the criteria of goals and health status, I suggest experimenting with the 8-hour fed/16-hour fasted periods. Eat quality foods to satiation in your eating window, especially focusing on the post-training period.

Keep in mind that IF is not for everyone, but it can be a powerful tool at certain times. Most importantly, even if IF isn’t for you, remember that you shouldn’t stress out if you miss a meal occasionally!

Additional Note/Addendum

Many readers have noted that this is similar to what Martin Berkhan does in his LeanGeans protocol. Martin Berkhan was certainly influential in the thought process behind this, and I don’t mean to take anything away from him. To be clear, LeanGains is much more complex than a 16:8 fasting:eating period. LeanGains involves calculating calorie intake, fluctuating calorie intake +20% on training day/ -20% on off days, macronutrient cycling (high carb/low carb), supplementing with BCAA's, etc. I didn’t use any of these techniques during my ten week experiment, I just ate to satiety during an 8-hour window. Martin is a great resource for people that want to learn more, especially on the body composition side of things. His website is leangains.com.

About the Author

Tyler Simmons is the owner and head Nutrition/Strength & Conditioning Coach at Evolutionary Health Systems. He has his bachelors in Kinesiology with a focus in Exercise Science and Exercise Nutrition from Humboldt State University. A former collegiate athlete, Tyler specializes in designing training and nutrition programs for athletes of all levels, as well as general population. Learn more at EvolutionaryHealthSystems.com.

Related Posts

Why You Should Never Take Nutrition Advice from Your Government

Anabolic Cooking: Why You Don't Have to Gag to Eat Healthy

References

1. Bellisle, F., & McDevitt, R. (1997). Meal frequency and energy balance. British Journal of Nutrition, 77, 57-70.

2. Mansell, P., & Fellows, I. (1990). Enhanced thermogenic response to epinephrine after 48-h starvation in humans. The American Journal of Physiology, 258, 87-93.

3. Staten, M., Matthews, D., & Cryer, P. (1987). Physiological increments in epinephrine stimulate metabolic rate in humans. American Journal of Physiology, Endocrinology, and Metabolism, 253, 322-330.

Sign-up Today for our FREE Newsletter and receive a four-part video series on how to deadlift!

|

| Read more |

|

| Last week, I published a guest blog on the topic of intermittent fasting. Brad Pilon, Author of Eat Stop Eat, contacted me shortly thereafter with respect to the previous blog in question, and I encouraged him to pull together a submission of his own on the topic. I’m all for hearing all sides of every argument – and you can find Brad’s perspective below.

I am largely known as the fasting guy, but what many people don’t know is that when I went back to school in 2006, I went back to “destroy” fasting.

After seven years working in Research and Development for a sports supplement company, I was ready to go back to school to complete graduate studies in Nutritional Sciences. My plan was simple. I was going to spend a couple years studying all of the rules of nutrition, and then I was going to write my own nutrition book.

After working in sports supplements for years, I thought I had a pretty good handle on exactly what I would find, the tricky part was figuring out where to start. After some thought, it became apparent to me that the obvious place to start my journey was to examine exactly what happens to the body in the absence of food – when we are fasting. Then, from there, I could start to investigate what happens when you eat different types of food.

I was positive that the research would clearly show that after a couple of hours of not eating your metabolism would slow down. This isn’t what I found.

Instead, study after study kept showing convincing evidence that even fasting for as long as 72 hours did not slow down your metabolism. This research was so convincing that I had no choice but to switch my plan and study the metabolic effects of short term fasting as the focus of my graduate work.

So, I can completely understand why someone might be mislead to believe that fasting for a period of 12-72 hours could drastically suppressed their metabolism. After all, I thought this myself for a long period of time. However, once I became educated on the topic I realized that this belief is simply not supported by the available published research.

So let’s take a look at the effect that fasting has on our metabolisms.

When we say metabolism, or “thermogenesis,” we are really talking about the amount of calories we burn, typically in a 24-hour period. Obviously, from a weight loss perspective we want this to be as high as possible, and any evidence that would suggest a diet might lower our metabolisms is definitely not ideal.

It has been a long held belief that our bodies quickly adapt to short periods of low calorie intake by lowering of our metabolism, but what does the research say?

When I looked at the metabolic effects of short term fasting, I was shocked to find that even when a person does not eat for THREE DAYS, measures of metabolic rate either remain the same or actually increase during this short period of fasting. This has been found by a large group of papers, including those by Mansell in 1990, Klein in 1993, Carlson in 1994, Webber in 1994, Zauner in 2000, and most recently Gjedsted in 2007.

In fact, the available body of research on short-term fasting is remarkably consistent in this finding: for both men and women, fasting for a period of 12-72 hours does not decrease metabolic rate.

To examine this even further, we can take a closer look at the paper written by J. Webber and I.A. MacDonald, specifically because it has a large number of subjects, and it included both men and women.

In this trial, all the people were studied on three different occasions after a 12, 36, or 72-hour fast. The studies were conducted in random order, and there was a gap of at least seven days of normal eating between each fast. Metabolic rate was calculated from a continuous recording of oxygen and carbon dioxide consumption and production, using a ventilated canopy (indirect calorimetry), which is a pretty standard measure of metabolic rate in research studies.

The results of this trial showed that not only was there NOT a decrease in metabolic rate, but that there was actually a significant INCREASE in resting metabolic rate between 12 and 36 hours of fasting.

We’re talking about roughly 100 calories, so nothing to get overly excited about, and I’m even willing to ignore this increase and say that while it was statistically significant, it’s probably not “real-world” significant. That being said, even when we ignore the increase in metabolic rate, we have to admit that there was definitely NO DECREASE in metabolic rate.

So, in men and women who fast for as long as 72 hours long, there is NO decrease in metabolic rate.

Based on this evidence, we can say that the practice of intermittent fasting (where a person fasts for 24 hours) will not decrease metabolic rate.

There are other questions that need to be answered about the benefits of fasting, including how it affects fat burning, hormones like growth hormone, and muscle mass.

For more information on the metabolic effects of short term fasting in humans, you can check out my book, Eat Stop Eat. |

| Read more |

|

This guest blog comes from Brian St. Pierre, a Cressey Performance staff member who specializes in nutrition. Keep an eye out for more great things from Brian; he's got a lot of excellent ideas and is very well-read.

Intermittent Fasting (IF) seems to be newest dietary fad. IF followers will choose a day or two each week, and on those days, they simply won’t eat for 24 hours. It seems simple, and a lot of people like the idea of giving your body and digestive system a break.

It also stands to reason that eating this way will help you eat less calories and make it easier to maintain a healthy body weight. Seems logical, right? Since IF usually leads to decreased calorie consumption it is often compared to Caloric Restriction (CR).

CR has been shown in a plethora of animal studies to lead to significant improvements in many markers of health and an increase in life span. Extrapolating that data, it would seem that if humans cut their calorie intake by 30-40% we would lead longer, healthier lives. Here arises the problem. In the animal studies with rats, researches observed signs of depression and irritability. With primates, it was even worse (researchers quantified the amount of monkey poo thrown for statistical analyses...okay, not really, but it's an amusing concept for future reference). If they did not consume enough cholesterol, they became violent.

So, angry monkeys aside, if you are willing to be cold, irritable, and prone to depression and flashes of violence, then caloric restriction is for you!

This is supposedly where IF comes in. More animal studies have shown that when animals were forced to fast every other day, but consume all they wanted on the off days, they were able to maintain their body weight, while also sustaining all the life prolonging benefits of CR. They had better glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity and blood pressure to name a few. It was the best of both worlds!

After these initial animal studies, human researches jumped on the IF bandwagon. People were expecting big things. Unfortunately, they were very disappointed with the results. Research started showing that people following IF, or even purposefully skipping a few meals per day were developing insulin resistance, decreased glucose tolerance, and increased blood pressure. These problems were not tremendous problems and some might argue that in real world IF, where people don’t fast every other day (only once or twice a week), the studied health problems wouldn’t occur.

Even if this is so, there is another problem with which we have to contend. The largest problem is a decrease in thermogenesis. Essentially saying that these people, even though they purposefully consumed as many total calories on IF as the control group, had drastically suppressed their metabolisms. This is why so many people have found such little real world fat loss from IF. In most real world applications - especially because people were eating diets in a significant caloric deficit - the body downregulated its thermogenesis to such an immense degree as to not allow for almost any weight loss. This to me is the final blow.

So, I guess if fasting is your thing, and it's not causing you any negative health effects, then have it. As for me, I prefer to stick to my low carb diet, eat whenever I feel like it, and receive all the benefits that IF proposes to give - except mine are real, not imaginary or hypothetical.

Note from EC: You can find a rebuttal to this post HERE.

So, angry monkeys aside, if you are willing to be cold, irritable, and prone to depression and flashes of violence, then caloric restriction is for you!

This is supposedly where IF comes in. More animal studies have shown that when animals were forced to fast every other day, but consume all they wanted on the off days, they were able to maintain their body weight, while also sustaining all the life prolonging benefits of CR. They had better glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity and blood pressure to name a few. It was the best of both worlds!

After these initial animal studies, human researches jumped on the IF bandwagon. People were expecting big things. Unfortunately, they were very disappointed with the results. Research started showing that people following IF, or even purposefully skipping a few meals per day were developing insulin resistance, decreased glucose tolerance, and increased blood pressure. These problems were not tremendous problems and some might argue that in real world IF, where people don’t fast every other day (only once or twice a week), the studied health problems wouldn’t occur.

Even if this is so, there is another problem with which we have to contend. The largest problem is a decrease in thermogenesis. Essentially saying that these people, even though they purposefully consumed as many total calories on IF as the control group, had drastically suppressed their metabolisms. This is why so many people have found such little real world fat loss from IF. In most real world applications - especially because people were eating diets in a significant caloric deficit - the body downregulated its thermogenesis to such an immense degree as to not allow for almost any weight loss. This to me is the final blow.

So, I guess if fasting is your thing, and it's not causing you any negative health effects, then have it. As for me, I prefer to stick to my low carb diet, eat whenever I feel like it, and receive all the benefits that IF proposes to give - except mine are real, not imaginary or hypothetical.

Note from EC: You can find a rebuttal to this post HERE. |

| Read more |

|

LEARN

HOW TO

DEADLIFT

- Avoid the most common deadlifting mistakes

- 9 - minute instructional video

- 3 part follow up series

|