Today's guest post comes from Dean Somerset, the creator of the excellent resource, Ruthless Mobility, which is on sale through the end of the day today for 60% off. Dean is a tremendous innovator and one of the brighter minds in the fitness industry today, and this article is a perfect example of his abilities. Enjoy! - EC

Mobility is one of those nebulous concepts that get thrown around the fitness industry a lot. You either have it or you don’t, and if you’re one of those lucky Tinman stiff-as-a-board folks who can’t touch their toes without a yardstick, you’re told to stretch and do more mobility work, which seems akin to carving out Mount Rushmore with nothing more than some sandpaper. We might be here a while if all you have available to you is simply stretching to make your mobility improve.

What we forget to do is ask a very simple question: Why do you feel tight in the first place? Muscles are incredibly dumb and won’t contract on their own. They’re usually told to contract, and they’re good soldiers that do what they’re told. You could cut a muscle out of the body and hook it up to a car battery and have it contract until either the proteins are ripped apart or until you turned off the battery. Also, muscles can’t get confused, so let’s stop using that term while we’re at it, shall we?

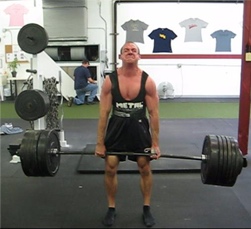

Typically a muscle will tense in response to a few different things. The first is the desire to produce movement, which means the normal shortening response happens and people awe and admire the massive weight EC pulls on a daily basis.

The second is as a protective means. A joint that may be unstable or a step away from being injured could cause the body to contract muscles around it in a protective “casting” method that restricts movement in the joint and calls up muscles that may cross more than one joint. An example of this would be the psoas tensing in response to anterior lumbar instability. The runners with chronic hip flexor pain and a forward lean when they pound the pavement, but who stretch their hip flexors (usually poorly and into spinal extension) 3 times a day for 20 years and still have tight hip flexors are a prime example of this. They stretch but don’t improve stability, so the psoas continues to hate life.

The third is in response to nervous system tone, specifically sympathetic and parasympathetic tone. Sympathetic is best exemplified by that one kid who is always bouncing and tapping their foot, can’t seem to sit still, and always wants to run and jump everywhere, whereas parasympathetic would be the stoner who looks perennially half asleep. If you’re constantly jacked up like a cheerleader on a mixture of crack and RedBull, flexibility won’t be a strong suit of yours, even though you could probably pull a tractor with your teeth or scare old women and small children.

The Ultimate Warrior was definitely NOT parasympathetic, nor was he likely to be hitting the splits anytime soon, but he could always bring the house down.

If you’re constantly a ball of stress, your muscles will be in a constant state of “kind of on,” which is to say their contraction is like lights on a dimmer switch. They’re not all the way on, but they’re not off either, they’re just “kind of on.” Being all jacked up all the time might sound cool, but in reality it tends to cause some issues if you can’t turn it down once in a while.

Lastly, and one of the most simple of all, is alignment. If you have a muscle held in a stretched position, it’s going to reflexively increase tension to prevent the muscle from stretching too far and potentially creating an injury.

I know it’s kind of counterintuitive that a chronically stretched muscle would be tight, but consider the effects of something like low back erector muscles and posterior pelvic tilt. If your pelvis is tucked under like Steve Urkel (I’m dating myself here, but it’s a fun game trying to confuse the 20 year olds), the erectors are already on stretch without having to do anything, plus they’re contracting to keep your spine from sliding further into extension. Trying to touch your toes will result in embarrassing results.

So now that you know why muscles can be tight, we can work on them and produce much better results.

Strategy #1: Change your breathing.

One of the first things I usually see when someone tries to stretch into a bigger range of motion than they’re used to is that they wind up holding their breath. This works against you in two ways. First, when you hold your breath, you crank up your sympathetic system, which drives more neural tone to all muscles of the body and causes reflexive tensing. Second, by not breathing you pressurize the entire thoracic spine: all of the intercostal muscles between your ribs, your diaphragm, and even your obliques tense to help increase intrathoracic pressure against that held breath. This causes muscles to hold tension even more.

In many instances, people will hit an end range of motion while holding their breath, and I tell them to breathe. They, in turn, gasp like they just surfaced from diving with Jacques Cousteau, and wind up getting another few inches into their range.

When trying to get range of motion, long deep inhalations and exhalations where you reach on the exhale makes a massive difference. The length of the breath increases stimulation of the vagal nerve, which is responsive to the heart and drives cardiac rate and parasympathetic stimulation into the medulla oblongata, and as a result muscle tension reduction through the whole body. Lower heart rates means a less energy demanding system, which is commonly results in lower arousal, meaning less tense muscles at rest.

Here’s a simple breathing drill you could do to help increase your overall mobility through your shoulders and hips.

Timely to give Eric a baby breathing exercise, huh?

Try this out: Test your toe touch ability and range of motion bringing your arms up over your head. Make a note of both how far you get and also how easy they both felt. One way to gauge overhead range is to stand against a wall, then bring your arms up overhead without arching your low back, and either mark the wall or make a mental note as to how high you bring your arms. Try the breathing drill and then retest your mobility and see whether it resulted in any changes.

Strategy #2: Build stability to create mobility.

As I noted earlier with respect to stability, if a joint is perceived as unstable and potentially about to be injured, the body will clamp down muscles around it. One way to see this in a graphic manner is to look at hip rotation and core function.

Try this out and see what happens: From a seated position, turn your hips side to side and see whether you have good rotational range of motion through both external rotation (where you look at the inside of your knee) or internal rotation (where you look at the outside of your knee). If you find you have poor external rotation, try doing a hard front plank and then retest. If you find you have a poor internal rotation, hit up a side plank and see what happens. Here's the test:

Here's the front plank:

Here's the side plank:

If you noticed a big increase in mobility, you likely had your hips putting on the brakes and donating some stability up to the lumbar spine. By reinstating some of that stability, the hips opened up and had lots of freedom since they weren’t working double time anymore.

Strategy #3: Change alignment from the bottom up.

Foot position can play a massive role in how well you move. Most people who tend to be flat footed wind up with tibial internal rotation, which results in internally rotated femurs. This rotation increases tension through the anterior hips and up the chain further which reduces the range of motion for overhead movements. It also reduces the force production capability through the legs, which makes you less awesome.

If you roll to the outside of the foot, more supination, you increase tension through the posterior aspect of the hip and pushes you into more external rotation, which reduces the amount of internal rotation your have available, and also reduces your ability to move freely down into hip flexion.

Use this little test and see what happens: stand up and roll your feet so that you put most of your weight on the inside, in line with the big toe, and bring your arms overhead and then touch your toes. Make a not of how high and low you go and also how easy they felt. Then roll to the outside of your feet, more weight on the baby toe side of the foot, and see what the movement results are looking like. You might find it’s different in each example, and will showcase how foot position can affect your overall mobility.

Strategy #4: Change alignment from the top down.

Neck position can play a HUGE role in not only arm movement but also hip mobility, and it plays down in a couple of simple anatomical means. For the shoulder, every muscle that holds the shoulder to the body and keeps it from falling down, is held up by the neck. If the neck is in a forward head posture, muscles like the sternocleidomastoid, scalanes, levator scapulae, and upper traps will be all jacked up. If you stand with your head jammed into the back of your neck, you’ll have some smashed up pteryhyoid and stylohyoid muscles, which will alter (not necessarily improve or decrease, but alter) the ability to move the arms around.

Secondary to this, head position will play a role in hip mobility due to the anatomical link to the spinal chord. The chord has the ability to slide up and down in the spinal canal in order to adjust for different positions. Since the nerves can’t stretch, they accommodate range differently by moving along with the rest of the body. When you’re in standing and you tuck your chin to your chest, the spinal chord moves up in the spinal canal. When you look up, your give some slack to the chord and it moves slightly lower.

What this means is that if you were to bend down to grab a bar for something like a deadlift, and you tucked your chin, your available range that the spinal chord could allow movement to occur before it was stretched would be less than if you had a neutral neck, and much less than if you were to look ahead slightly. Additionally, if you have any restrictions through areas like the sciatic arch, it will prevent movement of the nerve through this area and make your range of motion somewhat limited.

Try this out: stand tall and tuck your chin to your chest, then try to touch your toes. Right after, keep your head level with the horizon and try to touch your toes again and see where the change in range of motion comes from. If you noticed a pronounced change, it's time to get cracking on "packing the neck" during your training and everyday life.

Strategy #5: Clean up cranky fascial lines.

This is where some voodoo starts creeping in. The body is more than a collection of individual muscles that all connect to bones and do stuff. They have lines of action where multiple muscles along specific pathways will contract and relax together to produce movement. These pathways are visually represented through the work of Thomas Myers in his outstanding book Anatomy Trains, but can be shown in real time with some simple tricks.

One fun fascial line to work with is the spiral line. It’s a really cool powerful series of tissues and muscles that runs from one foot around the spine and connects to the opposing shoulder, both on the front and the back. By “tuning” fascia in the leg, you can see some pretty immediate changes in range of motion at the shoulder.

I showcased this with a live demo in a recent workshop in Los Angeles, where a participant had some shoulder issues. I had Tony Gentilcore of Cressey Sports Performance fame stretch him into external shoulder rotation, then applied some light pressure to his opposing adductor group to simulate what he would do with foam rolling. Within 5 seconds, he started to get more external rotation, all without me doing anything at his shoulder and with Tony only holding his arm in a position and letting gravity pull him down.

Try this out: If your shoulders are restricted through external rotation (like laying back to throw a baseball), foam roll your inner thigh, spending time hating life and breathing deep to try to get them to reduce tension and pain, then retest the shoulder external rotation. If you’re restricted through internal rotation, try rolling out your IT bands and see what happens.

Wrap-up

These methods aren’t guaranteed to work for every single person, but they are simple tricks that seem to work well with a lot of people. The good thing is if one of them works really well for you, you could use it on a regular basis to keep your mobility high and to use it in a new way you never had before.

Note from EC: If you're looking for more mobility tips and tricks - and the rationale for their inclusion in a program - I'd encourage you to check out Dean's fantastic new resource, Ruthless Mobility. Your purchase includes lifetime updates and continuing education credits. Perhaps best of all, it's on sale for 60% off through the end of the day today (7/4).

Sign-up for our FREE Newsletter to receive a video series on how to deadlift!

|