Today’s post is going to rub some folks in academia the wrong way. Therefore, I want to preface the piece that follows by saying:

a) I am a huge advocate of a multi-faceted education, encompassing “traditional” directed study (e.g., classroom education), self-study, internships, and experimentation.

b) I loved my college experience – both undergraduate and graduate. I benefited tremendously and made a lot of valuable connections.

However, it didn’t come easily; I got out of it what I put into it. To be candid, there are a lot of my peers who took the exact same courses and got the exact same degrees who didn’t walk away having gotten their money’s worth.

But, then again, does anyone really get their money’s worth?

College isn’t cheap nowadays. Check out the following statistics from CollegeBoard.com (as of 2011; this is sure to increase in the years to come):

- Public four-year colleges charge, on average, $7,605 per year in tuition and fees for in-state students. The average surcharge for full-time out-of-state students at these institutions is $11,990.

- Private nonprofit four-year colleges charge, on average, $27,293 per year in tuition and fees.

- Public two-year colleges charge, on average, $2,713 per year in tuition and fees.

Of course, this doesn’t take into account the cost of books, travel, food, accommodations, and the $5,000 in on-campus parking tickets you’ll end up paying. Educations can run upwards of $220,000 - and that's before you consider student loan interest and the opportunity cost of investing that money.

Assume 24-30 credits per year (12-15 per semester), you’re looking at a per credit hour cost of $399.66-$499.58 for public, out-of-state. It’d be $253.50-$316.88 for public, in-state. Public two-year colleges would be $90.43-$113.04. Finally, private would be $909.77-$1137.21. Sorry, Mom and Dad; I’ve never in all my years heard a kid say that an hour with one of his professors – even in a one-on-one context – was worth over a grand.

They also charge you to do internships elsewhere. In other words, you have to pay to get credits accepted – which means that the cost per hour you actually spend with college faculty is, in fact, even higher.

Many folks go to college to figure out what they want to do. Others go because it is a social experience that is both fun – and helpful in maturing them as individuals. That’s fine.

However, it is becoming tougher and tougher to consider it an investment, especially since the “success gap” between college graduates and those who don’t attend college is getting smaller and smaller. Along these lines, if you haven’t read it already, I’d strongly encourage you to read Michael Ellsberg’s New York Times piece, Will Dropouts Save America?

The exercise science field is one in which this success gap is arguably smaller than in any other. The barrier to entry to the personal training field is incredibly low; independent of schooling and previous experience, one can become certified in a matter of a few hours via an online test, and many gyms will hire people who aren’t even certified or insured. In fact, as I wrote a few years ago, Josef Brandenburg, a great trainer based in Washington, D.C., actually got his pet pug certified. The sad truth is that he could probably do a better job than most of the trainers out there who are pulling $100/hour.

Of course, I’m preaching to the choir here. Most of the folks reading this blog are educated and highly motivated to be the best that they can be. You seek out the best reading materials, DVDs, seminars, and colleagues from which you can learn. Personal training means a lot to people who grew up and went to college wanting to eventually help people get healthy, improve quality of life, optimize sports performance, or simply be more confident.

However, that doesn’t change the fact that our profession as a whole has become a “fall-back” career. It can be what college kids decide to do over summer vacation to make a few bucks, or what extremely well-paid lawyers or accountants take up when they get sick of long hours at desk jobs.

That doesn’t make them bad people; it just means that the minimal regulation in our industry has rendered a college education in this field a trivial competitive advantage in the workplace.

Additionally, this doesn't mean that college professors aren't qualified or doing their jobs sufficiently. It just means that the curricula that typifies an exercise science degree simply isn't sufficient to provide a competitive advantage over non-college-educated candidates in the workforce. There are exceptions, no doubt,in the form of outstanding professors who go above and beyond the call of duty to help student, but I can't honestly say that I've ever heard of a college kid coming out of any undergraduate exercise science program boasting of a competitive advantage that was uniquely afforded to him/her because of the education just completed. The closest thing might be a program with a strong alumni network that provides easier access to job opportunities.

Of course, the cream will rise to the top in any field – and that’s certainly true of exercise science as well. The industry leaders are, for the most part, people with college educations in exercise science (or closely related fields) – but the question one must ask is, “would these people have been successful in our field even without the courses they took in their undergraduate studies?”

Don’t you think Mike Robertson’s drive for self study would have sustained him in a successful career in this field even without a degree?

Don’t you think Todd Durkin’s energy, charisma, and passion for helping people would have shone through even if he hadn’t gotten a degree?

Moreover, I can list dozens of bright minds making outstanding headway in this field with “non-exercise-science” college degrees. John Romaniello (Psychobiology/ English), Joe Dowdell (Sociology/Economics), and Ben Bruno (Sociology) are all successful, forward-thinking trainers who come to mind instantly, and they’re just the tip of the iceberg.

Some of my best interns have come from undergraduate majors like English Literature, Acting, and Biology. We’ve had others who didn’t even have college degrees and absolutely dominated in their roles at Cressey Performance.

Guys like Nate Green, Adam Bornstein, Sean Hyson, Lou Schuler, and Adam Campbell don’t have college degrees in exercise science (although Campbell did get a graduate degree in Exercise Physiology following his undergraduate in English). However, from their prolific writing careers and by surrounding themselves with the best trainers on the planet, they’ve become incredibly qualified trainers themselves – even if they don’t have to train anybody as part of their jobs.

With all these considerations in mind, the way I see it, you’ve got three options to distinguish yourself in the field of exercise science – and I'll share them in part 2 of this article. If you’re a high school or college student contemplating a career in exercise science, this will be must-read material.

In the meantime, you may be interested in checking out Elite Training Mentorship, our affordable online education program for fitness professionals.

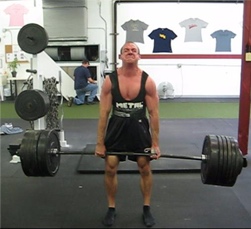

Sign-up Today for our FREE Newsletter and receive a four-part video series on how to deadlift!

|